Sonorous Prayers

Choral settings of biblical Psalms

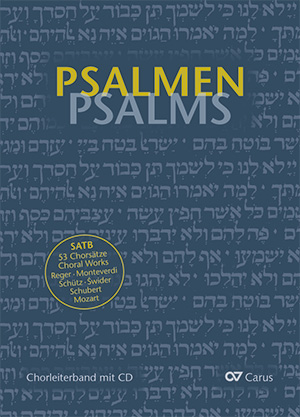

As suggested by the name "Psalm" (Ancient Greek for playing a stringed instrument; song), the poetical prayers compiled in the biblical psalter are fundamentally conceived within a musical context. These over two-thousand-year-old texts continue to inspire composers in many diverse ways up to the present day. In the new choral collection Psalms, you can discover a colorful spectrum of choral compositions from previous centuries up to the present day.

Music history would be much poorer without the existence of the 150 psalms. The wide range of musical settings of these prayers ranging from simple songs to the Symphony of Psalms and from Baroque psalm concertos to organ psalms cannot, however, be easily categorized within a uniform branch of music entitled "the psalm genre." We encounter psalms from many different epochs and in many different locations. Their origins go back to Jewish-Hebrew songs and the single-voice "tonal body" of Gregorian chants in which the music is entirely dedicated to liturgical declamation.

Martin Luther’s psalm settings – his first attempt with Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir (From deep affliction, I cry out to Thee) (Psalm 130) immediately achieved great popularity – are just as much part of psalm music as J. S. Bach’s motet for double chorus Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied (Sing to the Lord a new song) (Psalms 149 and 150, Claudio Monteverdi’s opulent Vespers 1610 and the Kleine geistliche Konzerte by Heinrich Schütz. What is more, psalms have acted as a significant source of inspiration not only for compositions, but also for improvisation.

"I spent the night alone and finally read the Psalms, one of the few books one can become completely absorbed in however absent-minded, distracted and challenged one is." In this passage from a letter dated 4 January 1915, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke speaks from the heart on behalf of many others. The history of lyrical poetry would also be far shorter without motifs and quotations from the Psalms. We only have to think of Nelly Sachs and Paul Celan or Arnold Schoenberg and his expressive poems collected under the title Moderne Psalmen. His last unfinished work for speaker, mixed choir and orchestra op. 50c is the musical setting of a psalm from this collection. The work breaks off after 68 bars with a verse by Schoenberg which could not be more typical for psalms: “Und trotzdem bete ich” (And yet I pray).

|

|

CHORAL COLLECTION PSALMS

|

The new Carus choral collection Psalms shows how ‘polylingual’ the musical settings can be. The texts range from the original Hebrew verses in works for Jewish synagogue music (Salomon Sulzer, David Rubin) via ecclesiastical Latin (Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and Claudio Monteverdi, more recently Józef Świder and Alwin Michael Schronen) and psalms utilized in Anglican Evensong (Thomas Tallis, William Boyce) and many other languages.

Salomon Sulzer (1804–1890): Was betrübst du Seele dich

Thomas Tallis (1503–1585): Man blest no doubt

Cyrillus Kreek (1889–1962): Mu Jumal

From a musical aspect, we can discover choral declamation as an

extension of the single-voice Gregorian model of singing psalms

(so-called psalm chants), chorale movements and also many forms of

polyphonic singing ranging from simple, contemplative Anglican chants

and Russian Orthodox homophony to virtuoso motets with a jazzy feel.

There are also a few surprises in the collection: it is not commonly known that Franz Schubert composed a setting of Psalm 92 in the Hebrew language for a service in the synagogue in the final year of his life. It is also not rare that psalm compositions touch on personal biographical elements as for example documented in Heinrich Schütz’s note in the preface of the Becker-Psalter after the death of his wife in 1625, citing composing as the “comforter” of his sorrow. In 1844, the Prussian king had just survived an assassination attempt unscathed and Felix Mendelssohn sent him “greetings and blessings” along with his famous choral piece Denn er hat seinen Engeln befohlen über dir (For He has commanded His angels to watch over you) which subsequently found its way into the oratorio Elijah.

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847): Denn er hat seinen Engeln befohlen

We not only encounter the composer Felix Mendelssohn in the new Carus

choral collection, but also his grandfather Moses who was literally

“Mendel’s son.” The great Jewish humanist translated the entire Psalter

into German and a text in his translation can be found in a choral

setting of Psalm 150 by Andreas Romberg, kapellmeister in Gotha, quasi

as the “final chord” of the 150 psalms..

If you embark on a journey of discovery in the new Choral collection Psalms, let it be accompanied by the fine words of Moses Mendelssohn. He recommends that you forget everything you have ever heard or read about the Psalms. What is far more important is the direct resonance in all emotional, rational and religious ‘keys’: "Select a psalm that harmonizes with your current state of mind." Martin Luther made a similar formulation: you will find words in the psalms which "rhyme with your concerns" as if they were solely created for you and which you could not have formulated better yourself. Here he was certainly also referring to the sounds of the "note setter" – i.e. composer – which constantly re-awaken the psalms to life.

Translation: Lindsay Chalmers-Gerbracht